Perfumes: The Future of Synthetic Colours

Colour Materiality

1868

From the 1860s the fruitful dialogue between science and art regarding synaesthesia brought about new ideas about the polysensoriality of colour perception. Conversely, advances in organic chemistry intensified the material dialogue between colour, sight, and smell. The history of synthetic colours is indeed closely related to that of synthetic perfumes. The industry and the raw materials were often similar, and the chemists who developed synthetic perfumes followed in the footsteps of those who developed synthetic pigments and dyes. Synthetic colours were therefore the precursors to synthetic scents.

It may be a coincidence that William Henry Perkin, who discovered mauveine in 1856, later invented coumarin in 1868, a scented synthetic molecule that is indistinguishable from its natural counterpart found in the tonka bean and is still widely used in perfumery and food applications. However, the connection between synthetic perfumes and colours is more obvious in the case of nitrobenzene or mirbane essence (Levitt, 2023). This product was presented at the 1855 Paris Universal Exhibition and described in the journal Le Génie industriel (Girard, 1855) as a substitute for the bitter almond oil used to perfume soaps. It is made by mixing nitric acid with benzene, an aromatic compound that played a key role in the synthesis of aniline.

Perkins wasn’t the only chemist to discover both new colours and new fragrances. The chemist Georges de Laire also began his industrial career by focusing on dyes, but the advances in organic chemistry that had provided perfumers with a range of new fragrances such as coumarin (1868), heliotropin (1869), and vanillin (1874) led him to create Edouard de Laire and Company in 1876 to exploit vanillin, another synthetic raw material that imitated the natural product. He quickly became one of the most important synthetic raw material producers in the history of perfumery (Briot, 2015).

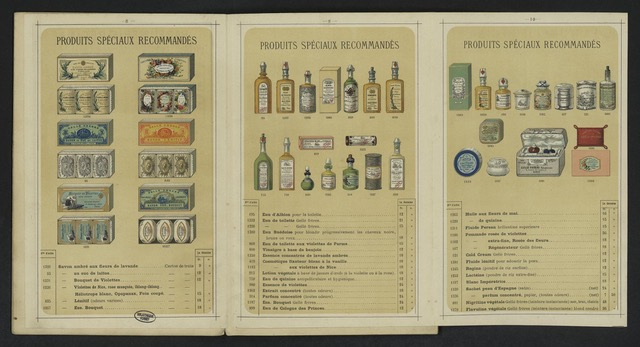

This relationship between the discoveries of organic chemistry in colours and scents became an assumed part of the history of the perfume industry (Girard and De Laire, 1873). However, if the extraction of a beautiful colour from a coal-derived product was perceived as the result of a charming or even magical industry, the chemical origin of scents remained a sensitive issue, as the sense of smell has been used to assess air quality. Consequently, newspapers often suggested that the transformation of matter by chemistry had the effect of deceiving about the true nature of materials. It was noted, for example, that the symptoms associated with inhaling an inferior perfume were the same as those associated with inhaling the odour of colours, since paint, dyes and synthetic fragrances are both made from turpentine or aniline. The chemistry of colour was thus a great inspiration to produce perfume, and many commercial products were made with synthetic perfumes and decorated with aniline ink, but the mixed reception of these new substances testifies to the chemophobia that has dominated the history of perfumery ever since.

Bibliography

-

Briot, Eugénie. « Imiter les matières premières naturelles. Les corps odorants de synthèse, voie du luxe et de la démocratisation pour la parfumerie du XIXe siècle », Entreprises et histoire, Vol. 78, N°1, 2015, pp. 60-73.

-

Girard, Charles, and De Laire, Traité des dérivés de la houille applicables à la production des matières colorants, Paris, Masson, 1873, pp. VII.

-

Girard, Charles, “Emploi de certaines essences artificielles”, Le génie industriel, Vol. 9, 1855, pp. 342.

-

Levitt, Teresa, Elixir: A Parusian Perfume House and the Quest for the Secret of Life, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2023.