Renaissance revival and chemistry: the colours of Italian maiolica

Colour Materiality

1855

In 1855, Italian neo-Renaissance maiolica was launched internationally by the Ginori manufactory at the Exposition Universelle in Paris.

The Ginori was the leading ceramics factory in Italy at the time. In 1848, it had come under the direction of Marquis Lorenzo Ginori Lisci, a chemist by training and a staunch supporter of the Italian Risorgimento, who introduced a new line of production based on the imitation of Renaissance maiolica, i.e. tin-glazed earthenware (Frescobaldi Malenchini and Rucellai, 2011).

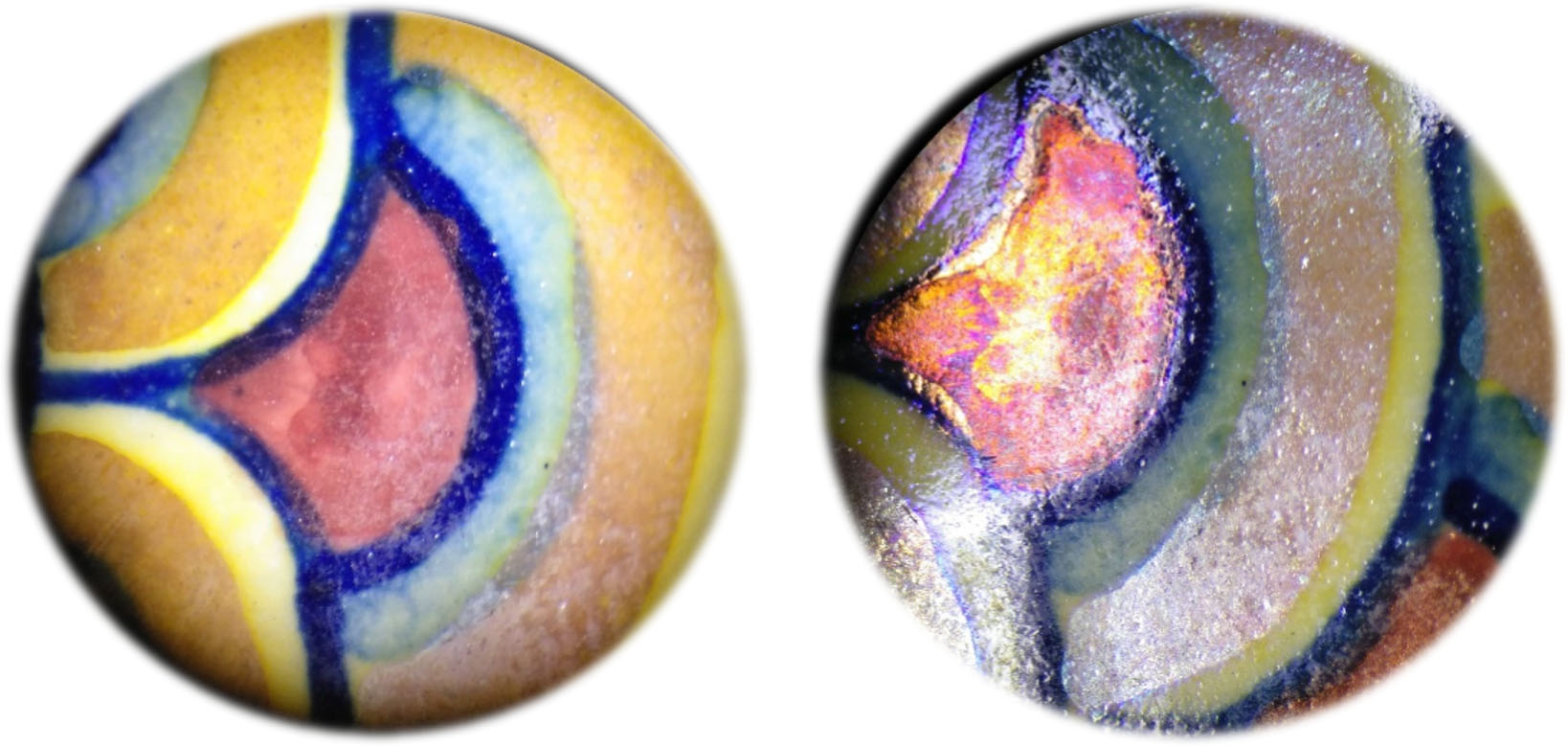

Colours were central to this revival: at the 1855 Exposition Universelle, the Ginori manufactory was officially recognised for the reproduction of the red and gold iridescent decorations typical of lustre (Fig. 1), a sophisticated technique that by the 19th century had been lost. This achievement was the result of extensive research and experimentation by Giusto Giusti and Francesco Giusti, the factory's chemist and painter, respectively.

To identify the composition of all the colours used in Ginori's revival maiolica a scientific investigation was performed (Manca, 2021). Eight Ginori wares made between 1855 and 1870, and now at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, were investigated using X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF) (Fig. 2). This is a non-invasive technique that allows to identify the chemical elements that make up the material under study.

The detected composition of the Ginori glazes closely resembles that of Renaissance maiolica, having lead and alkali as fluxing agents, tin as an opacifier, and typical metallic colourants like copper for green, manganese for brown, cobalt for blue, iron and/or antimony for yellow, and silver and copper nanoparticles for lustres. This precise reproduction was likely due to experimental rediscovery (as in the case of lustres) but also to the continuous use of traditional recipes in Italy (as in the case of simpler colours used also on table wares). In any case, the decision to use the original materials and techniques appears to be intentional. Notably, chrome green, one of the new pigments available thanks to the recent development of the chemical industry, was deliberately not used : factory records indicate that this pigment had been purchased since at least 1840, but it was not detected in any Ginori wares analysed.

However, the XRF analyses also showed that Ginori glazes were not identical to Renaissance ones. A significant difference is the presence of zinc in most analysed objects. While zinc occasionally appeared in trace amounts in Renaissance glazes, it was not common until the 19th century when refined zinc oxide became widely available and used in vitreous materials. Ginori’s decision to incorporate zinc oxide, despite its absence in traditional maiolica, likely stemmed from its advantageous properties: zinc oxide enhances the rheological and optical qualities of the glaze, offering significant technological and aesthetic improvements.

The compositional analysis showed that Ginori's revival of Italian maiolica involved a delicate balance of tradition and innovation, which is emblematic of the second half of the 19th century. The manufactory meticulously replicated Renaissance techniques and materials while selectively adopting new technologies to enhance their creations, exemplifying a programmatic revival of Italian Renaissance splendour intertwined with 19th-century advancements.

Bibliography

-

Frescobaldi Malenchini L., Rucellai O. (eds), The Revival of Italian Maiolica: Ginori and Cantagalli, Edizioni Polistampa, Firenze, 2011.

-

Manca R., Non-invasive, scientific analysis of 19th-century gold jewellery and maiolica. A contribution to technical art history and authenticity studies, Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Firenze, 2021.