The chromatic world of Alma-Tadema: an overview of his library

Colour Materiality

1868

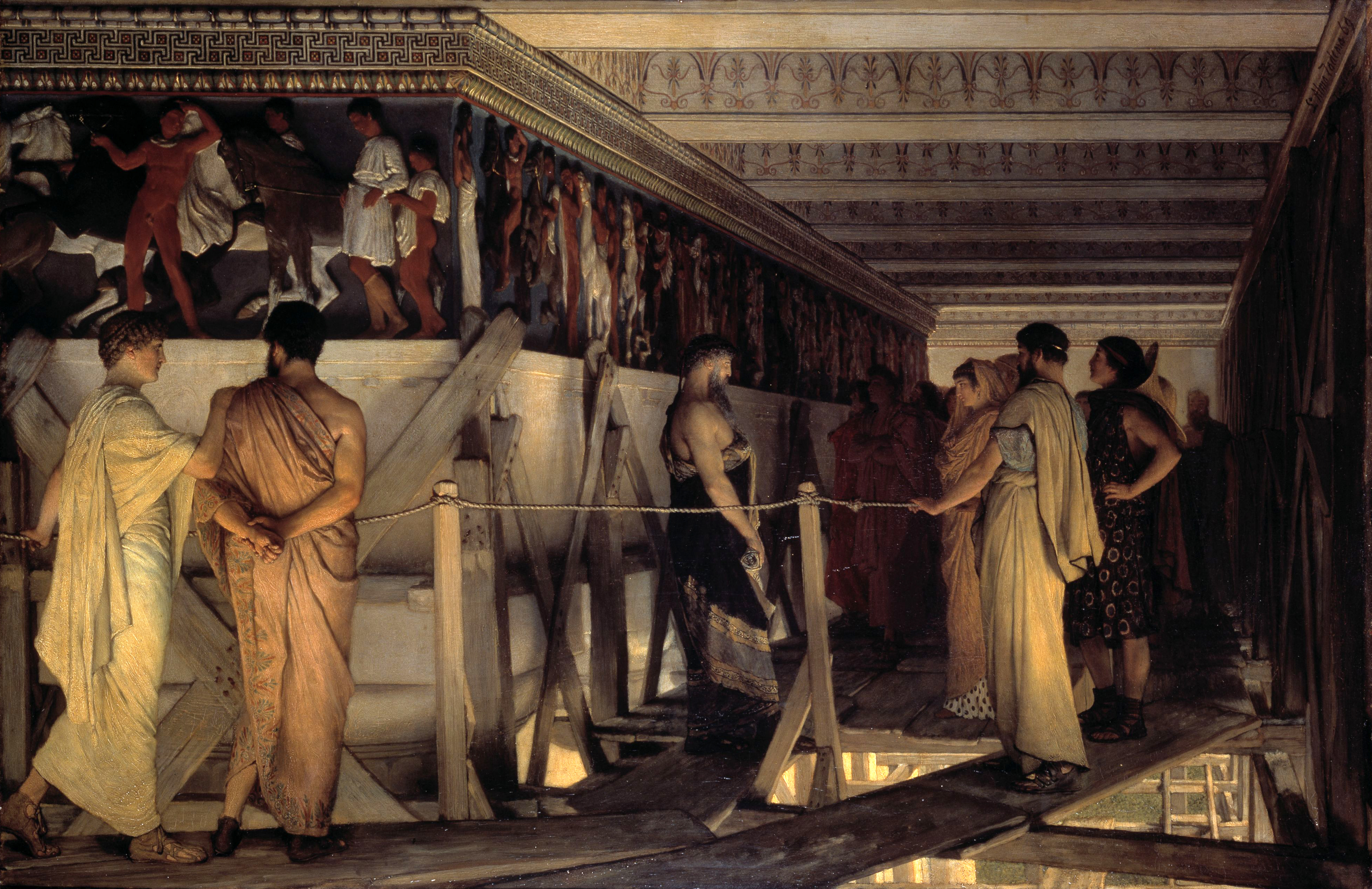

« As the sun colours flowers, so art colours life » was Victorian painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s motto, highlighting how important colour was to his conception of art. His 1868 famous painting, Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends (fig. 1) exemplifies the attention he paid to the colours of the past. The artist here depicts the construction of the Acropolis under the supervision of Pericles in the second part of the 5th century BCE. Two aspects are remarkable in Alma-Tadema’s work: first, the representation of a work-in-progress, instead of the magnificent edifice usually depicted, then the polychromy of the Parthenon frieze, partly on display at the British Museum. Alma-Tadema was aware of the recent discoveries related to ancient polychromy, as well as on the vivid debates brought about by the publication of Hittorff’s L’Architecture polychrome chez les Grecs (1851) which the artist had read. Alma-Tadema’s library is indeed a useful tool to understand his chromatic world. The artist was particularly interested in the science of colours: he owned Vibert’s essay, La Science de la Peinture, which – among others – focuses on the perception of colours according to light. In this regard, the chiaroscuro effect, highly visible in the 1868 painting, underlines the key role of light in the perception and recognition of the different chromatic hues. Alma-Tadema also visited the Crystal Palace at Sydenham for which architect Owen Jones designed a colourful reconstitution in plaster of the Parthenon frieze.

Besides, Alma-Tadema was well-known for his paintings of bacchanalia, described by John Ruskin as representations of “the last corruption of th[e] Roman state.” On a metaphorical level, the Bacchanalian world, characterized by a sense of frenzy, excess, and subversion, is highly colourful. In La femme dans l’Antiquité grecque, a book written by Gabriel de Roton, also present in Alma-Tadema’s library, the Bacchanalian festivities are described in the following terms: “Puis, après le cortège officiel, toute une théorie étrangement bigarrée : Satyres barbouillés de pourpre et de vermillon […].” The adjective “bigarrée” refers to a key notion in Victorian Aestheticism: the Greek poikilia, meaning multicoloured and conveying both desire and vitality. Moreover, the bacchanalian paintings of Alma-Tadema are synaesthetic: musicians and their instruments are carefully depicted while the sense of smell is evinced through aniconic and scented motifs, such as ritual fumes. The phenomenon of synaesthesia was of high significance to the artist: Alma-Tadema owned John Denis Macdonald’s 1869 book, Sound & colour: their relations, analogies, and harmonies (fig. 2), exploring the numerous interactions between music and colours. The musical titles of Alma-Tadema’s paintings from 1872 onwards certainly recall Whistler’s Symphonies and Harmonies.

Alma-Tadema’s collection of prints and photographs also sheds light on other chromatic sources of inspiration: the painter indeed owned several Japanese colourful woodblock prints. But unfortunately, Alma-Tadema never wrote much about the materiality of the pigments he used, as shown by the scarce records held by the Royal Academy of Arts (fig. 3), just mentioning copal varnish, turpentine and linseed oil.

Bibliography

-

Barrow, Rosemary, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, London: Phaidon, 2003.

-

Alma-Tadema Library. Hand List of Books prepared by the Victoria and Albert Museum, Birmingham, Cadbury Research Library, Special Collections.

-

De Roton, Gabriel, La Femme dans l’Antiquité grecque, Paris: Henri Laurens, 1901.

-

Didier, Michel, “Melody on a Mediterranean Terrace: Alma-Tadema’s Musical Life and Paintings,” in RIdIM/RCMI Newsletter, vol. 21, no. 1, 1996, pp. 19-28.

-

Grand-Clément, Adeline, “Poikilia”, in Pierre Destrée and Penelope Murray (ed), A Companion to Ancient Aesthetics, London: Blackwell, 2015, pp. 406-421.

-

Hittorff, Jacques Ignace, Restitution du temple d'Empédocle à Sélinonte ou L'architecture polychrome chez les Grecs, Paris: Firmin-Didot frères, 1851.

-

MacDonald, John Denis, Sound & colour: their relations, analogies, and harmonies, London: Longmans, 1869.

-

Prettejohn, Elizabeth, “Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends”, in Penelope Curtis (ed.), On the meanings of sculpture in painting [exhibition, Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, october 10, 2009 - january 10, 2010], Leeds: Henry Moore Institute, 2009, pp. 106-108.

-

Ribeyrol, Charlotte, « Homeric Colour : recherches sur la couleur chez les Esthètes anglais », in Marcello Carastro (ed.), L’Antiquité en couleurs. Catégories, pratiques, représentations, Grenoble: Éditions Jérôme Millon, 2009, pp. 43-61.

-

Ribeyrol, Charlotte, "Étrangeté, passion, couleur". L’hellénisme de Swinburne, Pater et Symonds (1865-1880), Grenoble: ELLUG, 2013.

-

Ruskin, John, The Art of England, Orpington, Kent: George Allen, 1887.

-

Vibert, Jehan Georges, La Science de la peinture, Paris: Paul Ollendorff, 1891 (6th edition).